| Home | A Focus on People | A Focus: Heath Center Committee Members | Keynotes and Educational Excellence | Black History Research | A Portrait of Black History: PAUL ROBESON | Heath Center Genealogy Division | The ... Heath Center Happenings ... Newsletter | Previews of Coming Heath Center Black History Events | 9/11/01 Aftermath | Directions to The Heath Center | Links, References, Vital Resources and More! | Heath Center Educational Interests Page | Contact Us | Music and Tributes | Heath Center Media Focus | Please Sign Our Guest Book | Heath Center Theological Corner | ||

|

An Annual Celebration of Black History in New Jersey

|

||

|

A Focus on People

|

||

|

This Page Salutes Those Who Have Made Truly Commendable and Note-Worthy Contributions in Our Nation and into Our Experience. |

||

|

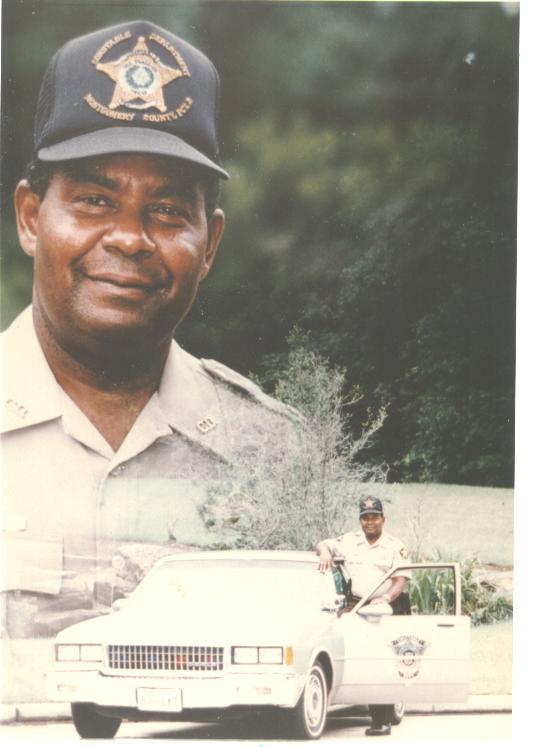

Deputy Spencer White |

||

|

|

||

|

When a 10-year-old Newark boy was killed after falling through an open elevator

shaft in the early 1970s, Lawrence Henry Hall was sent to the scene to talk to the family. A living room full of grieving

friends and relatives awaited him, creating a difficult situation for even the most seasoned reporter. Before delving into questions, however, Mr. Hall sensed a need to first show

some compassion. He broke away from the crowd, took the hands of the mother -- looking her straight in the eyes -- and spoke

some soothing words of comfort. "From that point on, through tears, she talked about her son in a way that

provided the information needed to tell her poignant story in her own words," recalled Stanley Terrell, a longtime colleague

and friend of Mr. Hall's at The Star- Ledger, who was with him that day and considered Mr. Hall both a mentor and a confidant.

Mr. Hall, who worked at The Star-Ledger for 34 years as a reporter, night

city editor, co-editor of Newark This Week and columnist, died Thursday morning at his home in Pennsylvania following a long

illness. A former resident of Montclair, Mr. Hall was 60. His journalism career was varied and saw him covering everything from the

riots of the 1960s to courtroom trials and city politics. One of the highlights was his coverage of the 1970s murder trial

of Mario Jascalevich, a Bergen County physician identified in the media only as "Dr. X" in the early stages of the case. Jascalevich was accused of killing three patients with injections of curare,

a muscle relaxant, at Riverdell Hospital in Oradell. He was acquitted in 1978 after a trial that lasted nearly three years.

Raymond A. Brown, the defense attorney on the case, described Mr. Hall as

a talented writer and reporter with high journalistic standards. "Larry was a hardworking guy. He was a man of the people and he was so intuitive

as a reporter. He would make a story sing," Brown said. Mr. Hall joined The Star-Ledger in 1970, becoming one of just two black reporters

in the newsroom at the time, the other being Terrell. He always enjoyed discussing topics of the day with friends and people

of all backgrounds. As a columnist, he would write about everything from controversial topics like capital punishment to the

simpler things in life, such as the beauty found in the advent of Spring. "He was an intellectual genius ... a real communicator and people person who

was so diverse in every subject," said Newark Mayor Sharpe James, who recalled having many stimulating conversations with

Mr. Hall over the years. Never one to back down from any story as a reporter, the soft-spoken Mr. Hall

had a humble response to an angry local elected official who confronted him after he wrote a scathing piece about the inner

workings of Newark city government. He simply wanted to make him a "good public servant," Mr. Hall replied. A lover of jazz and other types of music, Mr. Hall confessed in one of his

last columns that he was admittedly from the "old school." He still owned a 12-inch black-and- white television set and a

"30-something stereo with real, honest-to-goodness knobs." Then there was his love for the outdoors, which saw this former city dweller

buying a farm house in Pennsylvania almost 20 years ago and transforming himself into a farmer. On his more than 35 acres,

he grew everything from vegetables and lilacs to fruit trees. "That was one of his favorite things, surveying the land on his tractor, seeing

what changes needed to be made. He loved it here," said Linda, his wife of 31 years. Born and raised in Elizabeth, Mr. Hall once recalled that there were "few

options back then for young black men." When a guidance counselor suggested he not even bother with college preparatory courses

and instead take up a trade, he was determined to defy her low expectations of him. "Secretly, I vowed to show the counselor and anyone else that they could not

define my limitations," he wrote in a 1999 column, part of a series of childhood reflections by six Star-Ledger columnists.

After high school, Mr. Hall would eventually enroll in Rutgers University,

working as a reporter for radio station WOR to help pay his way through school. He was about a year or so away from graduating

when a French teacher berated him in front of an entire class of white students for showing up late. "I left her class, and that's the last time I've been to college, except for

an occasional seminar. I vowed to become a writer on my terms," wrote Hall, whose father had his own dry cleaning business.

As the late 1960s developed into a turbulent decade where executives in all-white

newsrooms were looking to hire black reporters to go out into inner-city neighborhoods rocked by unrest, Mr. Hall found work.

He reported for media outlets like WOR and the New York Daily News, and would cross paths with some of the most noted civil

rights leaders of the day, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. One of the accomplishments Hall was especially proud of was becoming a finalist

for a White House fellowship. The rigorous selection process required him to travel to Washington D.C., where he had an audience

with Lady Bird Johnson. "He was so pleased that this black kid from Elizabeth, with no college degree,

could even be doing this," said his wife. Besides his wife, also surviving are a daughter, Kelli Vega of Raleigh, N.C.;

a son, Laquan of Toms River; his mother, Elizabeth, of Cranford; three brothers, Gary, Edward and Lloyd, and two sisters,

Sandra Reynolds and Jacqueline, all of whom live in New Jersey. A viewing and prayer service for Mr. Hall was held Monday at the Hessling

Funeral Home, 428 Main St., in Honesdale, Pa. on October 4, 2004 from 3 to 6 p.m. A Memorial Service was held on Tuesday, October 5, 2004 from

5 to 8 p.m. at the Love of Christ Church, 1608 Porter Rd., in Union, N.J., officiated by Reverend Ellis Smith and Minister

Ronald Brangman. Larry and Linda Hall had recently donated an antique Thrasher from their

Honesdale, Pennsylvania Lilac and Nursery Farm to the Heath Farm Homestead in Middletown, New Jersey. Be sure to visit the

Heath Farm home page by clicking on the highlighted link below:

"Don't come in the back lookin' for nothing," David announces. "When I break this line down, that's it."

He may sound like a field general barking orders to hungry troops, but David, is only half serious. The retired

produce purchaser has volunteered here for seven years and his goal is to help others.

Everyone is welcome at the Lunch Break, which opens its doors at noon every day except Sunday. Eduardo, a

29-year-old laborer who recently moved to Red Bank from Mexico, said he has made new friends here. Lawrence Scott, 60, says he has been coming to the Lunch Break since it opened on West Bergen Place in 1986.

"I like the way the staff handles the people who come here, and Mrs. Todd looks out for everybody," says Scott,

a former horse groomer who was forced to retire because of asthma and an allergy to hay.

Todd, was the wife of a retired diplomat, James, recently deceased, (himself an active member and presenter

for the Bertha C. Heath Black History Committee), who has lived throughout the world and is fluent in several languages,

commands a great deal of respect at the Lunch Break, which is much more than a soup kitchen.

Though the Lunch Break normally serves about 100 meals a day, the crowd is smaller today, primarily because

Todd has succeeded in finding jobs for many of her clients at area supermarkets.

"It's a rewarding job and I enjoy being here," she says.

Yes, those who work at the Lunch Break feed the hungry. But they also nourish souls and minds and provide

a wide array of social services. Today, 12 meals are delivered to home-bound senior citizens and disabled people.

John, a retired maintenance worker with a bad back, takes advantage of the chiropractor who regularly visits

the Lunch Break to provide free treatments.

Free eye examinations are available, and visitors are encouraged to borrow books, which are stacked in neat

rows on a makeshift bookcase of milk crates.

In the basement, Inice Hennessy is busy sorting through garbage bags filled with donated clothing, which is

given away free each Saturday.

Todd's pantry is stocked with canned food, laundry detergent, hot cocoa and dry goods. Shopping carts are

filled with groceries and given to needy families. All that Todd asks in return is that one family member work two hours of

community service.

There is never a shortage of volunteers at the Lunch Break.

Ann Byron arrives each morning at 8 a.m. and has been cooking meals here for eight years.

"I love to see the people get a good meal," says Byron, a retired nurse's assistant.

Neil Gallagher, a retired harbor pilot from Wall, works once a week. Ed Freedman, a retired salesman from

Matawan, serves food and scrubs dishes once a month. Lunch Break’s mission is being accomplished: Those who need the aid of the soup kitchen and pantry are

being fed and getting the needed groceries, despite the highly publicized recent developments, according to those affiliated

with the facility. In addition to providing food for the needy, Lunch Break also assists people in obtaining various

social services for which they are eligible. "People are falling through the cracks," said Frank Dunn, who has been volunteering at the soup kitchen for

seven years. "But Lunch Break fills those cracks." Lunch Break is looking at different ways to raise funds, Poku said, including a campaign to get people to

donate old vehicles, which can be sold to raise cash. Lunch Break’s additional problem is that it lacks someone who can write grants in order to obtain funding

from private foundations and other entities. Norma Todd contended that while donations may have fallen off, "We’re going to make it." Lunch Break will be holding some events to help raise money, including a Chinese auction and a spaghetti dinner,

she said. Lunch Break was established in 1986 to feed the area’s hungry and assist those who were incapable of

helping themselves. Since then, the nonprofit organization has grown to become a food pantry as well as a site to help people

navigate their way to needed social services. Todd said between 15 and 20 students from area schools, some as far away as Asbury Park, came to help out. Students from Red Bank Regional High School’s Black American Cultural Association were some of those

who participated. The 10 Red Bank Regional youth who helped serve lunch were participating in the Kindness and Justice Challenge

2001. That initiative was developed by the Do Something Fund, a national nonprofit community development organization. The purpose is to inspire young people to honor the memory of King by having them get involved in community

activities. The student members of the association also had been conducting a coat drive for the last two weeks. That

clothing was donated to Lunch Break and is scheduled to be distributed to needy families and individuals in the area. "We’re trying to change the culture here," explained C. Arthur Albrizio, the school’s principal.

"We’re trying to get the kids more active in the community, especially on a day like this." If "YOU" or someone you know can help Lunch Break by "giving of their

time and expertise" and writing grants to help this compassionate organization to obtain the funds they need to continue

to serve, please email your contact information to:

|

||