|

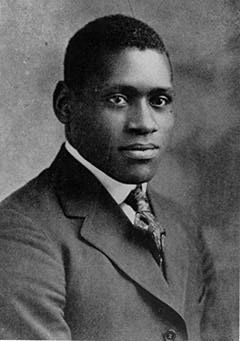

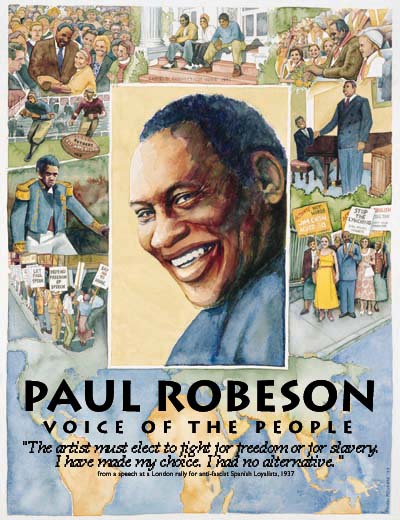

Paul Robeson (1898-1976)

Paul Robeson was a famous African-American athlete, singer, actor, and advocate for the civil rights of people around the

world. He rose to prominence in a time when segregation was legal in the United States, and Black people were being lynched

by racist mobs, especially in the South.

Born on April 9, 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, Paul Robeson was the youngest

of five children. His father was a runaway slave who went on to graduate from Lincoln University, and his mother came from

an abolitionist Quaker family. Robeson's family knew both hardship and the determination to rise above it. His own life was

no less challenging.

In 1915, Paul Robeson won a four-year academic scholarship to Rutgers University. Despite violence

and racism from teammates, he won 15 varsity letters in sports (baseball, basketball, track) and was twice named to the All-American

Football Team. He received the Phi Beta Kappa key in his junior year, belonged to the Cap & Skull Honor Society, and graduated

as Valedictorian. However, it wasn't until 1995, 19 years after his death, that Paul Robeson was inducted into the College

Football Hall of Fame.

At Columbia Law School (1919-1923), Robeson met and married Eslanda Cordoza Goode, who was

to become the first Black woman to head a pathology laboratory. He took a job with a law firm, but left when a white secretary

refused to take dictation from him. He left the practice of law to use his artistic talents in theater and music to promote

African and African-American history and culture.

In London, Robeson earned international acclaim for his lead role

in Othello, for which he won the Donaldson Award for Best Acting Performance (1944), and performed in Eugene O'Neill's Emperor

Jones and All God's Chillun Got Wings. He is known for changing the lines of the Showboat song "Old Man River" from

the meek"..I'm tired of livin' and 'feared of dyin'....," to a declaration of resistance, "... I must keep

fightin' until I'm dying....". His 11 films included Body and Soul (1924), Jericho (1937), and Proud Valley (1939).

Robeson's travels taught him that racism was not as virulent in Europe as in the U.S. At home, it was difficult to

find restaurants that would serve him, theaters in New York would only seat Blacks in the upper balconies, and his performances

were often surrounded with threats or outright harassment. In London, on the other hand, Robeson's opening night performance

of Emperor Jones brought the audience to its feet with cheers for twelve encores.

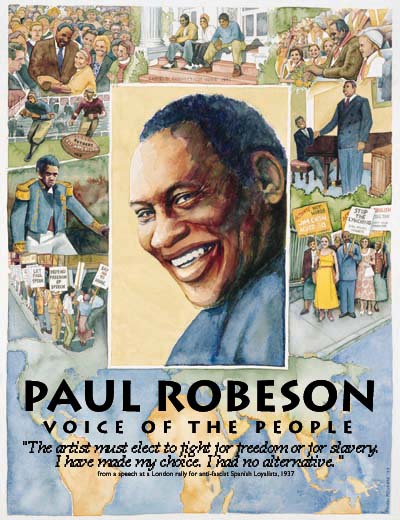

Paul Robeson used his deep baritone

voice to promote Black spirituals, to share the cultures of other countries, and to benefit the labor and social movements

of his time. He sang for peace and justice in 25 languages throughout the U.S., Europe, the Soviet Union, and Africa. Robeson

became known as a citizen of the world, equally comfortable with the people of Moscow, Nairobi, and Harlem. Among his friends

were future African leader Jomo Kenyatta, India's Nehru, historian Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, anarchist Emma Goldman, and writers

James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. In 1933, Robeson donated the proceeds of All God's Chillun to Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler's

Germany. At a 1937 rally for the anti-fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War, he declared, "The artist must elect to

fight for Freedom or for Slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative." In New York in 1939, he premiered in

Earl Robinson's Ballad for Americans, a cantata celebrating the multi-ethnic, multi-racial face of America. It was greeted

with the largest audience response since Orson Welles' famous "War of the Worlds."

During the 1940s, Robeson continued to perform and to speak out against racism, in support of labor, and for peace. He was

a champion of working people and organized labor.

He spoke and performed at strike rallies, conferences, and labor

festivals worldwide. As a passionate believer in international cooperation, Robeson protested the growing Cold War and worked

tirelessly for friendship and respect between the U.S. and the USSR.

In 1945, he headed an organization that challenged

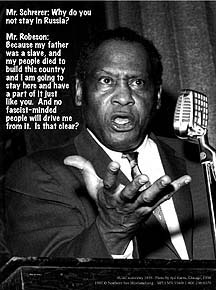

President Truman to support an anti-lynching law. In the late 1940s, when dissent was scarcely tolerated in the U.S., Robeson

openly questioned why African Americans should fight in the army of a government that tolerated racism. Because of his outspokenness,

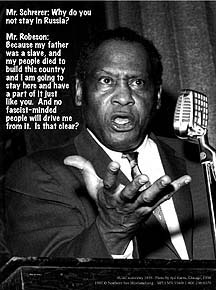

he was accused by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) of being a Communist.

Robeson saw this as an

attack on the democratic rights of everyone who worked for international friendship and for equality. The accusation nearly

ended his career.

Eighty of his concerts were canceled, and in 1949 two interracial outdoor concerts in Peekskill,

N.Y. were attacked by racist mobs while New York State Police officers stood by.

Robeson responded, "I'm going

to sing wherever the people want me to sing...and I won't be frightened by crosses burning in Peekskill or anywhere else."

In 1950, the U.S. revoked Robeson's passport, leading to an eight-year battle to resecure it and to travel again.

During those years, Robeson studied Chinese, met with Albert Einstein to discuss the prospects for world peace,

published his autobiography, Here I Stand, and sang at Carnegie Hall.

Two major labor-related events took place

during this time. In 1952 and 1953, he held two concerts at Peace Arch Park on the U.S.-Canadian border, singing to 30-40,000

people in both countries. In 1957, he made a transatlantic radiophone broadcast from New York to coal miners in Wales.

In 1960, Robeson made his last concert tour to New Zealand and Australia.

In ill health, Paul Robeson retired

from public life in 1963. He died on January 23, 1976, at age 77, in Philadelphia.

REMARKS BY HARRY BELAFONTE ABOUT PAUL ROBESON to the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives and friends celebrating

the 60th anniversary of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade's arrival in Spain.

The event was held at Boro of Manhattan

Community College, 199 Chambers St at West St, New York City, on Sunday, April 27, 1997, at 2:00pm.

This is a transcription

of an audio tape recording of the event.

Harry Belafonte was intrOduced by Henry Foner, Master of Ceremonies and

Retired President of the Fur and Leather Workers Union Joint Board.

Harry Belafonte:

[prolonged applause]

Thank you very much. Thank you. When I came in, and looked around, I saw groups of people related to this afternoon's events,

most of them looking somewhat older than myself ... [laughter] ... all smoking!

I mean, I never saw so many cigarettes

in my life! And I was thinking, you know [...] when you'd have generations of future anti-fascists [??] set a better example!

As a footnote I would like to tell you that I, selfishly, would like to see each and every one of you, live for

another hundred years! [applause]

I've had occasion to say this before, and I'll make it very brief, as I say it

again. As a young boy growing up in the streets of Harlem in the United States, the idea that fascism should be everyone's

concern, and should be confronted vigorously, came to me very early on.

Central to that understanding was the heroism,

and the bravery expressed, by the thousands of men and women all over the world who volunteered to be in the International

Brigades to fight against fascism on the European continent.

They have been compared, on such excursions, as romantic

adventurers. Certainly, to those of us who were profoundly affected by that contribution, there was no romance to it, although

there was great adventure.

There was something almost more profound. It was a truth that engulfed the universe. It

said that fascism anywhere is a threat to people everywhere. [applause]

And I, much to the consternation of many

of my fellow servicemen, I, at the age of 17, volunteered to fight in the Second World War. I joined the United States Navy

knowing fully well that what I was doing was only enhancing and carrying forth the mandate that had been given by those who

had fought in Spain. (applause]. When I came out of the war .. I was mustered out of the service . . and thought that being

an artist would be my calling . . . or the calling to be an artist was my thought . . [laughter].

It is interesting

to me that I should have been blessed in those early years of decision-making by having been embraced by a man who had a profound

effect on my life . . . Paul Robeson. [long applause] And it was from Paul that I learned [singing]: "Viva la Quince

Brigada, Rumbala, rumbala, rum-ba-la." And it was from Paul that I learned [singing]: "Los Quatros Generalos."

And it was from Paul that I learned that the purpose of art is not just to show life as it is, but to show life as

it should be. And that if art were put into the service of the human family, it could only enhance their betterment.

Paul said to me, he said, 'Harry, get them to sing your song, and they will want to know who you are. And if they want

to know who you are, you've gained the first step in bringing truth and bringing insight that might help people get through

this rather difficult world.'

Shortly before he died, I visited him in Philadelphia. He was living at his sister's.

And I looked at this giant of a man who was, quiet frail in body, but still strong in spirit. And through all that had engulfed

him -- McCarthyism, the difficult times that he faced in this country because of his beliefs, because of his resistance to

oppression -- I looked at him, and I said, 'Paul, I must know. Was all that you have gone through, really worth it? Considering

the platform you had gained, and how easy life could have been for you, was it worth it?' And he said, `Harry, make no mistake:

there is no aspect of what I have done that wasn't worth it. Although we may not have achieved all the victories we set for

ourselves -- may not have achieved all the victories and all the goals we set for ourselves, beyond the victory itself, infinitely

more important, was the journey.'

To the men and the women [applause]...to the men and women whom I've met along

the way, Paul made the difference. Paul's strong center, his strength, and his power, and his gift, was the fact that he stood,

in Spain, with the Lincoln Brigade, and sang in Madrid, at the height of the war in Spain.

That valor, and the valor

of all the men and women who fought there, lives on. I've been to Rwanda. I've been to Zaire. I've been to South Africa. I've

been to many places in the world. Wherever I see the resistance to tyranny, the resistance to oppression, I know that a banner

is being carried forth, and will be waved high...the banner waved by the predecessors who fought in the International Brigade

against fascism. There is nowhere in the world I go, where I see people resisting oppression, that I am not led to understand

and believe, and know, that the standard was set for all of us by the Volunteers and what they did to bring to the world the

bigger picture about where we were headed in the 20th Century.

I appreciate the invitation that was extended to me

to be here, not just so much to make you feel good about yourselves, but to make me once again have the privilege of moving

among you and feeling good to myself.

Thank you -- and long live the Brigade and what it stands for -- and long

live each and every one of you -- and give up smoking!

[Turning back to the audience as he exits to long applause]:

Fidel Castro gave it up, you can give it up!

RESOLUTION IN SUPPORT OF THE PAUL ROBESON CENTENNIAL

Whereas, April 9, 1998 will mark the 100th birthday of Paul

Robeson, great actor, athlete, scholar and fighter for the civil rights of people throughout the world; and

Whereas,

Paul Robeson, son of a runaway slave rose to prominence when segregation was legal in the U.S. and Black people were being

lynched by white mobs; and

Whereas, Paul Robeson's life of achievement in so many spheres made him truly one of this

century's Renaissance figures whose life should be heralded as a role model for young people everywhere; and

Whereas,

Paul Robeson in his travels pursuing his acting and singing career, met future leaders of the anti- colonial movements in

Africa and Asia, used his great talents to share his own people's culture along with that of others, to benefit the social

movements of his time, and sang throughout the world for peace and justice in 25 languages; and

Whereas, as Paul

Robeson's political consciousness grew with the rise of fascism in Europe, he donated the proceeds of All God's Chillun to

Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler in 1933, traveled to Spain the next year to support the anti-fascist forces in that country's

civil war declaring that "The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice.

I had no alternative"; and

Whereas, Paul Robeson spoke out strongly for the rights of working people throughout

the world--in support of the Ford workers in Detroit, against passage of the Taft- Hartley Act in the United States, for the

coal miners in Wales, the oppressed workers in South Africa and on behalf of so many others; and

Whereas, Paul Robeson

was made an honorary member of many unions including ILWU, Actors Equity, the Marine Cooks and Stewards, the National Maritime

Union, the Transport Workers' Union, and State, County and Municipal Workers of America; and

Whereas, Paul Robeson

because of his outspokenness against racism and colonialism, for peace and the rights of working people was accused by the

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) of being a Communist and this accusation along with the State Department's revocation

of his passport in 1950 for a period of eight years (until it was restored by action of the Supreme Court) nearly ended his

career; and

Whereas, the persecution which Paul Robeson suffered during the McCarthy Era represents the types of

actions the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights were designed to prevent, Paul Robeson was denied this

protection and sacrificed his fame and fortune and endured great personal hardship to stand fast for the principles in which

he believed; and

Whereas, Paul Robeson to this day remains world famous outside the United States, yet has been tragically

almost forgotten in the land of his birth, and is virtually unknown among our youth for whom he could serve as a role model

of the highest quality for his courage, dignity, and integrity; and

Now, Therefore Be It Resolved that [insert name

of appropriate labor body] endorse the efforts of the Paul Robeson Centennial Committee to celebrate the 100th Anniversary

of Paul Robeson's birthday by stimulating activities to gain public recognition for the life, career and legacy of Paul Robeson

and to emphasize activities that will recognize his contribution to the struggle of working people throughout the world and

to educate young people about Paul Robeson and especially his support for the rights of labor; and

Be It Further

Resolved that [insert name of appropriate labor body] request [insert name of next higher body], to adopt this resolution.

Paul Robeson Jr., son of famed actor, singer and athlete, Paul Robeson Sr., recalls the legacy of his father. Robeson Jr.

spoke on the 25th anniversary of the Paul Robeson Cultural Center.

Paul Robeson also honored the memory of his father

as he appeared as the Keynote Speaker at one of the many annual Black History Celebrations at the Heath Center, hosted by

the Heath Center Black History Committee.

|